I have a great new job, allowing me to spend several weeks recently in the center of the universe, and I’m loving it. I’m going to spend even more time there from now on.

By that I mean Palo Alto, Silicon Valley’s capital and VMware HQ, where I am now Senior Director, National Technology Strategy, working primarily with the R&D team. But I can’t help putting that “Valley capital” term in a bit of historical context. Back in ancient times (late ’80s-early ’90s) when I worked for the Mayor of San Jose, S. J. City Hall was dealing with a bit of civic insecurity. Although San Jose’s population was already larger than San Francisco and now the tenth largest city in the country, our mayor (my boss Tom McEnery, the first government leader ever elected to the Silicon Valley Business Hall of Fame) believed that we needed to brand the city explicitly as “The Capital of Silicon Valley.” So that became a multi-million-dollar marketing campaign, and we punched the message home every chance we got.

Yet as the mayor’s policy adviser and speechwriter, I laughed each time I used the phrase. I had just moved to San Jose from Palo Alto, where I got a graduate degree at Stanford. Just twenty miles up Highway 101, Palo Alto had much better claim to being the center of the geographically hazy electronics domain. I knew the arguments we used in San Jose (see here for example). But I also had already met Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard in person in Palo Alto, and ha d walked many times on the sidewalk by the legendary garage at 367 Addison where HP was born in the late 1930s; and I had also seen a different historic marker four blocks from the garage, at the corner of Channing and Emerson, commemorating Palo Alto’s very first electronics startup – Federal Telegraph Company, founded in 1909.

d walked many times on the sidewalk by the legendary garage at 367 Addison where HP was born in the late 1930s; and I had also seen a different historic marker four blocks from the garage, at the corner of Channing and Emerson, commemorating Palo Alto’s very first electronics startup – Federal Telegraph Company, founded in 1909.

Palo Alto itself has spawned thousands of startups for many many decades, and it never stopped. Fast forward to the turn of the millenium just 20 years ago, when Microsoft and Amazon were trying to shift attention to Seattle/Redmond, Palo Alto struck back and fostered yet another legendary Valley startup: VMware – now my new home. Here’s the origin context for VMware, from an official history of Stanford Research Park:

It can be said that one of the cornerstones of Silicon Valley was laid when Varian Associates broke ground as Stanford Research Park’s first company in 1951. The Stanford Industrial Park, as it was first called, was the brainchild of Stanford University’s Provost and Dean of Engineering, Frederick Terman, who saw the potential of a University-affiliated business park that focused on research and development and generated income for the University and community.

Dean Terman envisioned a new kind of collaboration, where Stanford University could join forces with industry and the City of Palo Alto to advance shared interests. He saw the Park’s potential to serve as a beacon for new, high-quality scientists and faculty, provide jobs for University graduates, and stimulate regional economic development.

In the 1950s, leaders within the City of Palo Alto and Stanford University forged a seminal partnership by creating Stanford Research Park, agreeing to annex SRP lands into the City of Palo Alto to generate significant tax revenues for the County, City, and Palo Alto Unified School District.

Throughout our history, an incredible number of breakthroughs have occurred in Stanford Research Park. Here, Varian developed the microwave tube, forming the basis for satellite technology and particle accelerators. Its spin-off, Varian Medical, developed radiation oncology treatments, medical devices and software for medical diagnostics. Steve Jobs founded NeXT Computer, breaking ground for the next generation of graphics and audio capabilities in personal computing. Hewlett-Packard developed electronic measuring instruments, leading to medical electronic equipment, instrumentation for chemical analysis, the mainframe computer, laser printers and hand-held calculators. At Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), innovations such as personal work stations, Ethernet cabling and the personal computer mouse were invented. Lockheed’s space and missile division developed critical components for the International Space Station. Mark Zuckerberg grew Facebook’s social networking platform from 20 million to 750 million people worldwide while its headquarters were in the Park.

Today, Tesla’s electric vehicle and battery prototypes are developed and assembled here in its headquarters. Our largest tenant, VMware, continues to create the virtualization hardware and software solutions they pioneered, leading the world in cloud computing. With over 150 companies in 10 million square feet and 140 buildings, Stanford Research Park maintains a world-class reputation.

In the summer of 2017, I got an email from a former Microsoft research colleague and one of the most eminent leaders in American technology R&D, David Tennenhouse. David has held key leadership roles in dream positions over the past quarter-century – everyone has wanted him on their team. He was Chief Scientist at DARPA; a research professor at MIT; President of Amazon’s R&D arm A9; VP & Director of Research at Intel; a senior leader in Microsoft’s Advanced Strategy and Research division. Smart companies have wooed him in serial fashion. Now David is VMware Chief Research Officer building and leading a stellar team, and over several months into 2018 we had some great conversations about where VMware had been and was going, and what I could bring to that journey. I had a chance to speak with several of the dozens of Ph.D.s he has been hiring to flesh out a comprehensive R&D agenda. I excitedly joined recently and we’ve been off to the races.

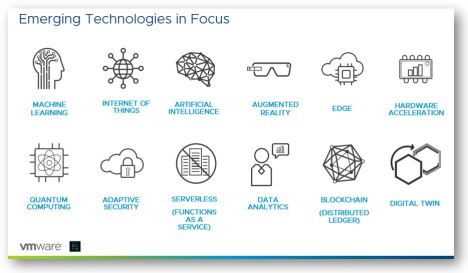

For a 20-year-old startup, the company’s growing like gangbusters (the stock market obviously still loves it), and it ranks high every year on lists of Best Employers. But what really attracted me was the stress on R&D and innovation culture, driving an unbelievably ambitious vision. I had always been impressed by VMware’s early virtualization technology; at DIA we were pioneering federal customers fifteen years ago, and wound up using it as a foundation of what would become our private cloud infrastructure. But VMware scientists and research engineers took virtualization much further, with abstraction becoming almost addictively popular. After the server and the OS were virtualized, so was storage, and then networks, and then the data center itself. Now our research agenda is energetically broad, across the following areas:

In fact, any large complex orchestration of resources, hardware, and processes may actually be just the next big virtual machine. We intend to build it, with disruptively great software. In 2011, web pioneer and Netscape cofounder Marc Andreesen wrote a famous manifesto in the Wall Street Journal, “Why Software is Eating the World”:

“More and more major businesses and industries are being run on software and delivered as online services—from movies to agriculture to national defense. Many of the winners are Silicon Valley-style entrepreneurial technology companies that are invading and overturning established industry structures. Over the next 10 years, I expect many more industries to be disrupted by software, with new world-beating Silicon Valley companies doing the disruption in more cases than not.”

That’s why I smiled last month, just after joining VMware, when our CEO Pat Gelsinger rebuffed talk of him moving to Intel as that company’s new CTO. He began his career  at Intel, was its first-ever CTO and the father of the fabled -486 processor. But today he’s virtualizing the world’s computational resources, and Pat tweeted his response to a CNBC anchor’s comments about the Intel CEO job: “I love being CEO of VMware and not going anywhere else. The future is software!”

at Intel, was its first-ever CTO and the father of the fabled -486 processor. But today he’s virtualizing the world’s computational resources, and Pat tweeted his response to a CNBC anchor’s comments about the Intel CEO job: “I love being CEO of VMware and not going anywhere else. The future is software!”

I still intend to live in Virginia and work closely with DC government friends and colleagues on research, reflecting the Valley’s traditionally close working partnership with the federal government. In fact, if you’re in a government position and are wondering “What’s going on inside VMware Research labs?” – drop me a line 🙂

Filed under: Government, innovation, R&D, Technology | Tagged: Government, history, research, research and development, Silicon Valley, Technology | 7 Comments »